The work is a multimedia narration exploring stories and memories of industrialisation between Belgium and Italy. The resulting installation comprises a series of photographs, archival material and a sound recording, outlining the story of a fictional character, a man now living in Belgium who is the son of Italian immigrants working as miners and who moved after WWII. Through different voices, languages and media, the project addresses issues of mobility and displacement, hope and nostalgia, memories in the present and the past.

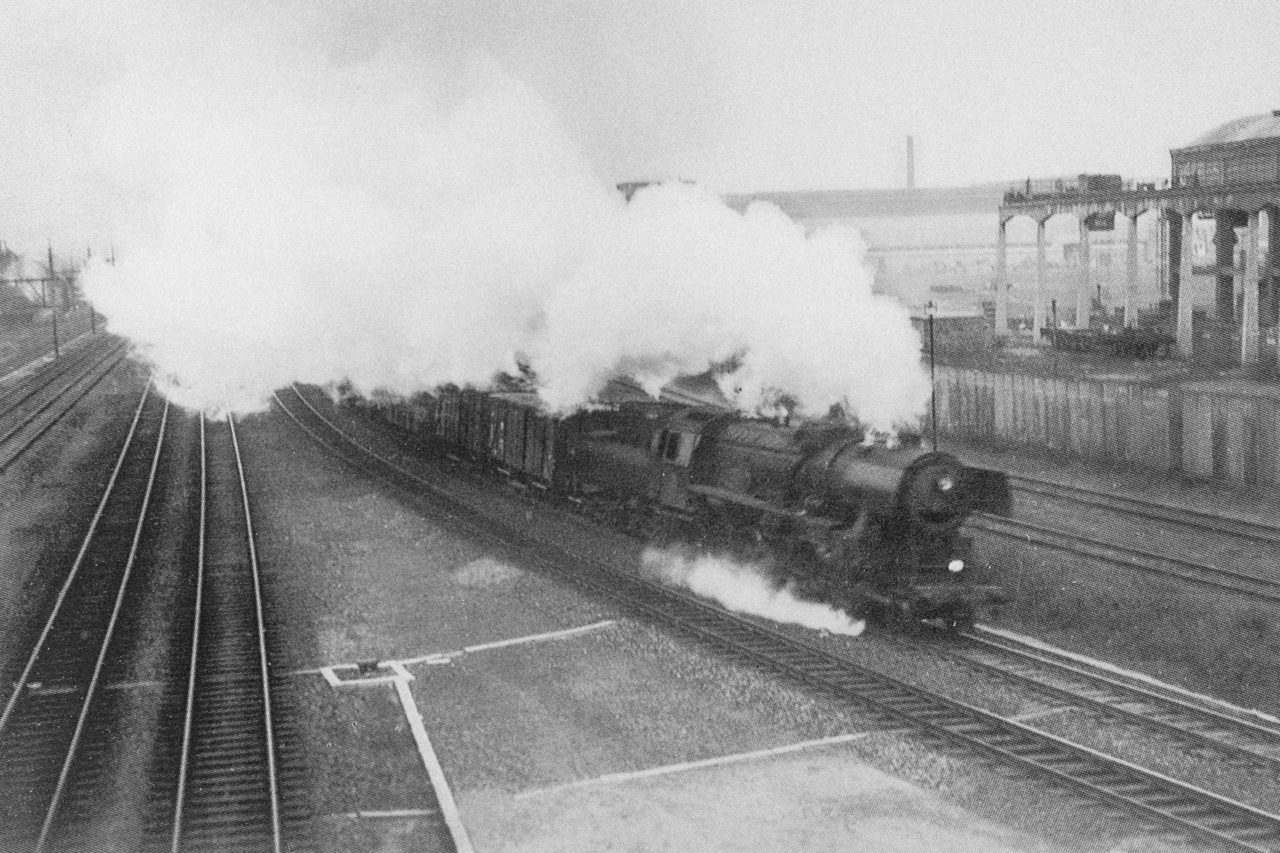

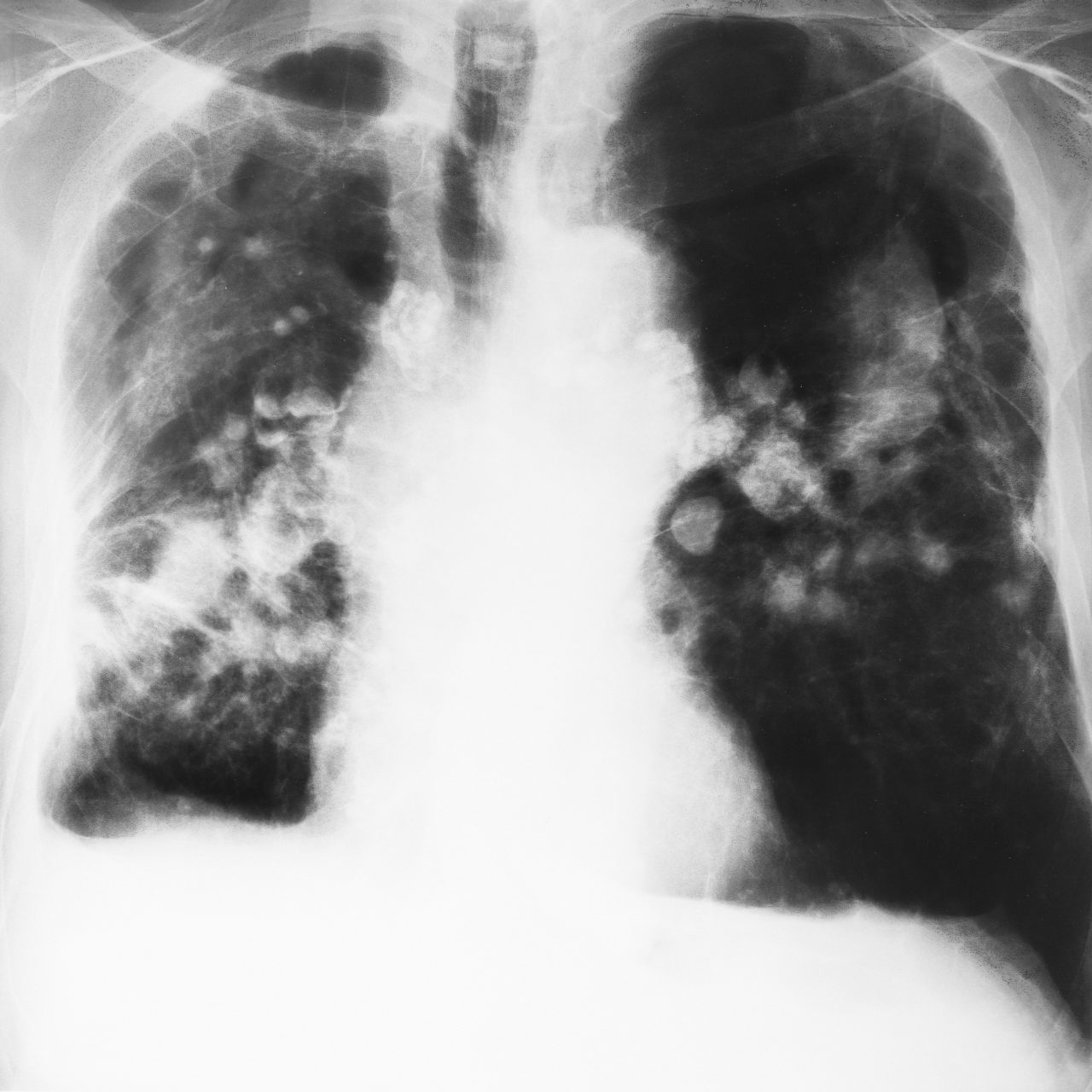

In common imagination, Italian emigration was a “spontaneous” phenomenon in which millions of people decided to go and work and live in other European countries, or even other continents, to escape hunger. In reality, this phenomenon was much more complex. At various times, it was actually the Italian state that literally sent its citizens to work in other countries, negotiating the conditions of their emigration, sometimes even paying their travel expenses and favoring through bilateral agreements with other states the placement of workers even before their departure from Italy. This phenomenon reached its peak in the post-war period, when the country had little work to offer and few economic resources for recovery. An example case of this is the Italo-Belgian agreement of 1946, which caused thousands of young people to leave Italy to go and work in the coal mines of Belgium. Theoretically the agreement also stated the working, living and salary conditions of the miners who, however, once arrived on site, soon realized how different they really were. One of the historical and biggest mines was near Charleroi, in Marcinelle where in 1956, following a fire and then an explosion due to human error, 263 men died, 136 of whom were Italians. Marcinelle can be considered an Italian “difficult memory”, even if it does not constitute a conflict or a war or a political massacre, but because it preserves the story of thousands of Italians who died on the job that had been presented to them as an opportunity to get a better life, but which in reality was instrumental in the procurement of raw materials that gave an enormous boost to the young Italian republic. Dans mon souvenir, c’était blanc partly constructs a theater of memory of that terrible event. The project does not describe, but merely evokes, bringing out sharp, clear and isolated images, enhanced by archive pictures and dreamlike visuals. It is not necessary to describe in order to remember, memory is not a monolith that answers each question clearly and decisively, but it is an image that appears and can take on the most diverse nuances depending on who is looking at it.

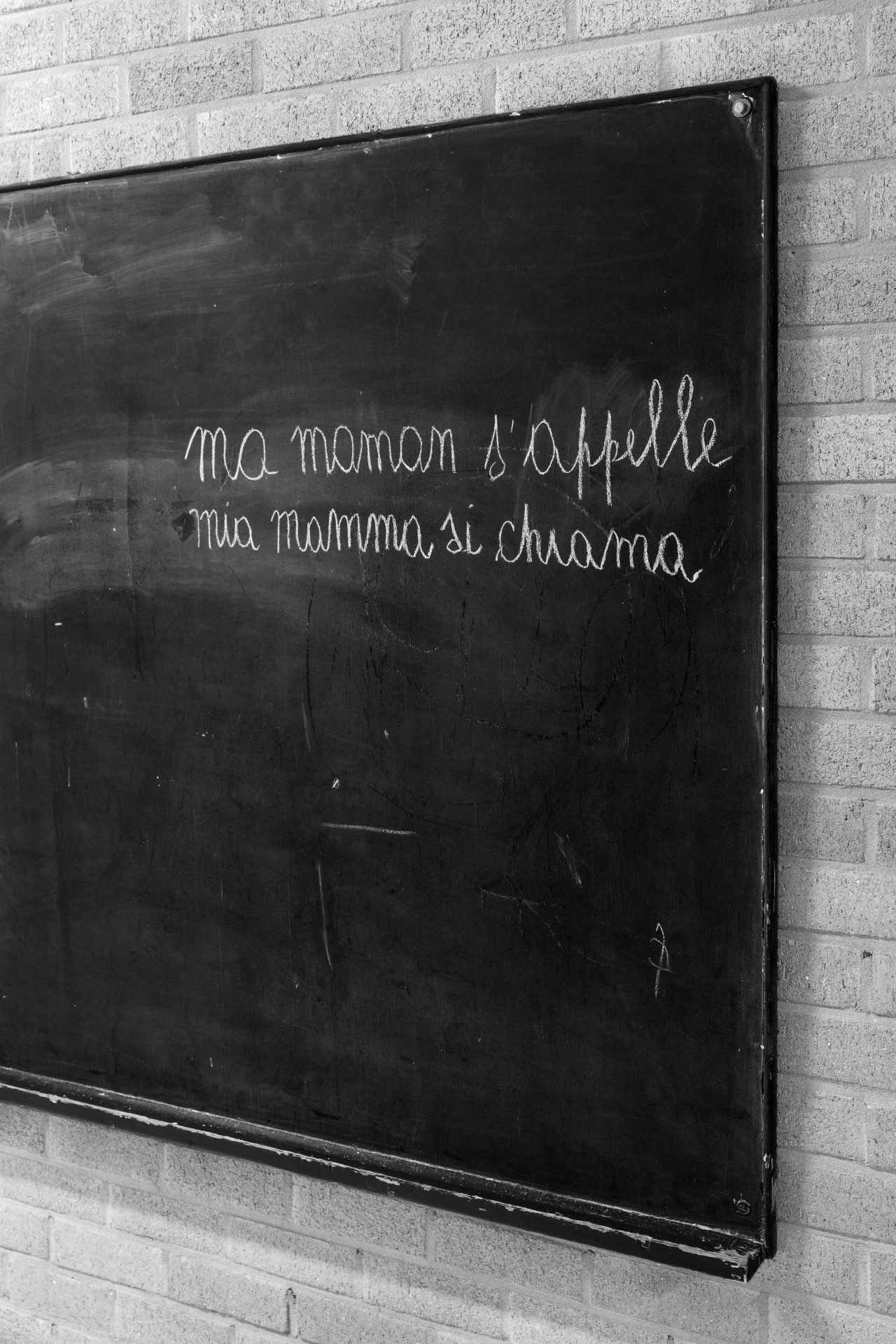

The work runs on two tracks: a visual one, in the foreground, and one of writing and audio that serves as a background. The work takes its title from a research of Prof. Anne Morelli, an expert on Italian emigration to Belgium, who after conducting numerous interviews with Italians who had emigrated to Belgium, noticed that one of the first memories of those who arrived in the country was the idea that everything was covered in snow. A memory that did not always correspond to reality, but that somehow was collectively imprinted in the minds of those arriving from southern Italy who landed in a very cold, northern country. For this reason, white becomes a recurring color, and takes different forms:

– a lamb, symbol of sacrifice but also a reminder of pastures as a child and of the pastoral Italy of the post-war period and of my childhood;

– a canary clutched by a pale hand, which on the one hand expresses extreme fragility, and on the other reminds of the little birds that were kept in mines to signal the lack of oxygen and avoid the slow death of miners from asphyxiation;

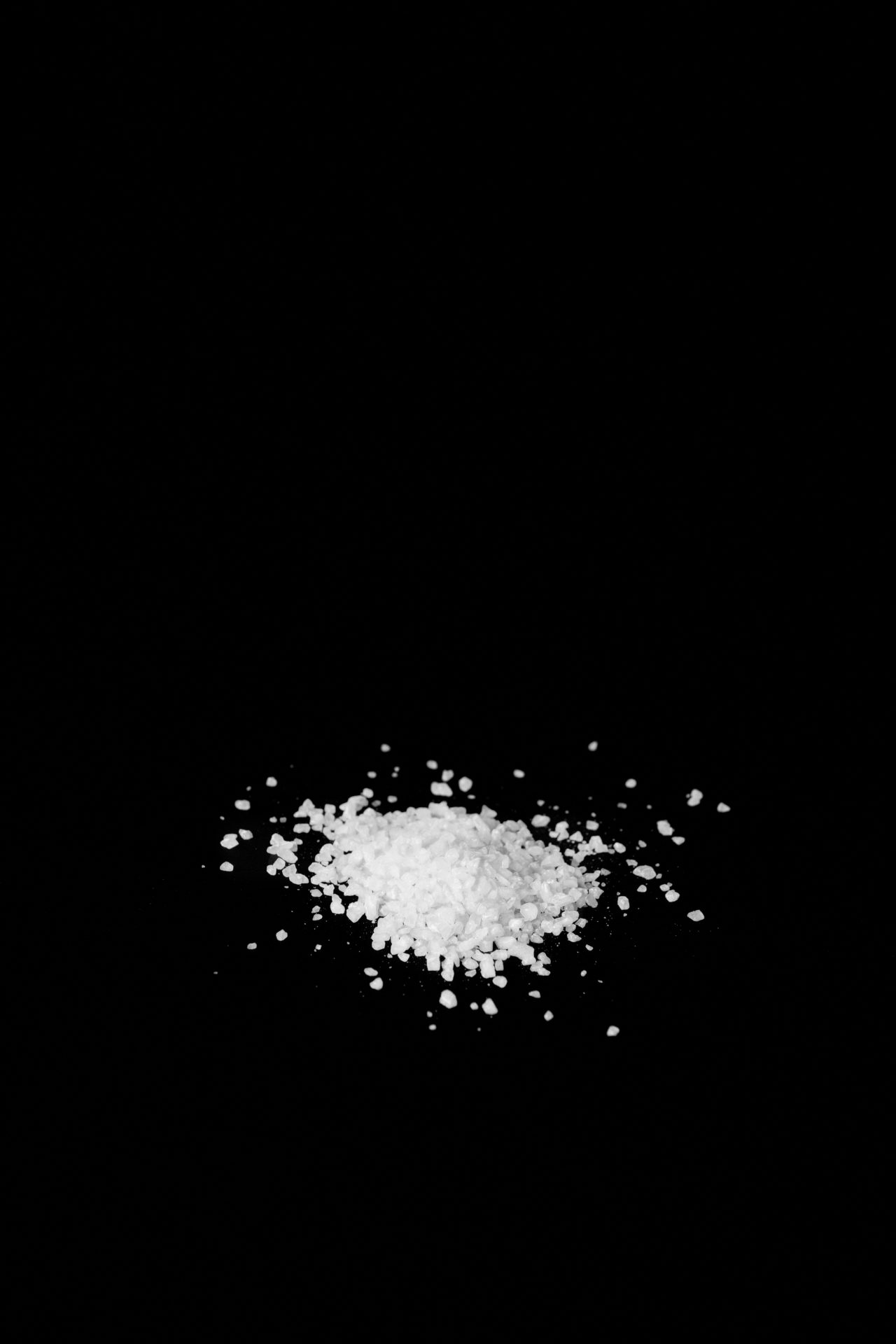

– a heap of white crystals that still makes one think of snow, but also of salt, which represented having climbed the social ladder for those coming from the countryside, a food for the “rich” according to poor peasants.

In contrast to the whites, are the blacks: of the terrills, the charcoal pits and the dark landscapes of Wallonia. The face of an old man – with a flashlight on his miner’s helmet, and a face that seems to be made of coal – reminds us that the memory of what once was affects everyone, not only those who have never returned from those mines. Next is the photo of the terril, the artificial hills created by the accumulation of coal mine slag, which become part of the Belgian “natural” landscape and a symbol of the senseless impoverishment of the earth. The work does not follow a formal logic, but uses the different formats of the images to build an architecture of feelings. The images are meant to be an invitation to venture into the narrow paths of our personal memories, as Serena does with hers. In fact, Dans mon souvenir, c’était blanc is not only the story of Italian post-war emigrants to Belgium, but it is also the artist’s story, as an emigrant from Abruzzo (Italy) to Brussels. Collective memories of Italian migrants and Vittorini’s intimate childhood flashbacks are merged to create a new identity. In the audio that accompanies the project we can hear the voice telling us about pastoral Italy and terrils, but we can’t understand to whom those memories belong, because the memories of the artist’s childhood are mixed with the memories of the miners she collected during the project’s research.

If you hear an old man’s voice right now, it is because I am indeed old. And without a properly functioning body, then what is an old man good for if not to remember? I can’t always remember well. I’m always missing something. Many things, in fact… maybe because my mother didn’t remember them either. I’ll tell you what I know, then. I know that my name is Antonio, and I know that when I came home they were staring at me, the ones who stayed. I don’t remember much of the village. The bells… my grandmother’s kitchen… the smell of the soil… the fence that ran along the horizon, where the sun falls asleep. The fresh milk, only just milked, that grandpa used to put in my mouth directly from his wrinkled thumb. I dream of the time we used to play during the day, between the alleys or along the river, and at night by the pastures. The nights were truly ideal for chasing each other and scaring each other off. It was like when we thought that above the antenna, those two red slits tearing the darkness apart were the eyes of a wolf. And I really believed it, that wolves had eyes made of embers and giant teeth. The ones that stayed were staring at me probably because I no longer belonged with them. But what was the point of telling them that I hadn’t run away? That I didn’t know where else to go but home? They introduced me like this: “This is Antonio, he speaks French and he is the son of a miner”. But I didn’t understand, I was confused. At night, I would dream of being the son of a miner. The earth, black, had given birth to me. And I dreamt of them, looking at me, intrigued and perplexed, next to the church. Their voices were coming out from the bell tower, they seemed to be holding me back, but they kept chasing me away. “Eat some bread, Antonio, where you are, it doesn’t taste so good. Drink the milk, Antonio, there’s none so good where you live.”